Carbohydrate, Training Prioritization

Andrew Berry / December 28, 2013

Most guys following the typical bodybuilder diet will start their day with a meal high in protein and carbohydrates. (1) Egg whites and oatmeal has been a staple of many iron enthusiasts for years. The idea behind this tasty meal is that the body has been through a 7-10 hour long fast overnight and muscle glycogen stores have been depleted. Eating a meal rich in protein and carbohydrates should be just what the body needs to kick start both the repletion of muscle and hepatic glycogen and initiate new muscle protein synthesis. The eggs provide the amino acids needed to synthesize muscle tissue while good old-fashioned oats raise insulin levels, driving the glucose (energy) and amino acids into muscle cells.

In previous years, I used to be of the same thought process- that the body absolutely needed carbohydrates in the morning. But, due to some informative research articles and an experiment in carbohydrate back-loading that I did on myself, my opinion has changed completely.

For the last few years, the majority of my carbohydrate intake has been consumed around my workout time. The goal was to still make gains in strength and muscle but to stay leaner on more a regular basis. This plan has not only allowed me to stay leaner by utilizing fat for fuel earlier in the day but has also yielded amazing muscle gains while at the same time improving my mood, cognition and even providing better sleep. I call this strategy carbohydrate prioritizing.

Carbohydrate Prioritizing

- Majority of carbs around training time to amplify the anabolic effect that training plus nutrients have on your body.

- Carbohydrate-free meals earlier in the day for enhanced fat loss.

- Improved clarity, mood and cognition.

- Better sleep due to the increased serotonin release closer to bedtime.

- Don’t think of your workout as a time to burn fat. It’s the time to stimulate muscle growth.

The goal of carbohydrate prioritizing is to put the carbs to work for you. Ideally, all the carbs we eat would go toward glycogen replenishment, energy and maybe most importantly, not towards new fat synthesis. If you eat the majority of your carbs at the right time, you will store glycogen, provide energy for anabolic muscle building reactions all while allowing your body to burn fat throughout the earlier hours of the day.

But wait, you might ask. Don’t carbohydrates give us energy? Wouldn’t a diet void of carbohydrates early in the day leave me dragging my feet? These were my initial concerns as well that will quickly be put to bed. But first, let’s talk a little about carbohydrates and insulin.

Carbs and Insulin

Yes, carbohydrates give us energy. The starch in carbohydrate is broken down into glucose units where they will enter the bloodstream and have a variety of fates. In response to carbohydrate intake, the pancreas produces insulin. Insulin is an anabolic peptide hormone that initiates glucose uptake by the various cells of the body.

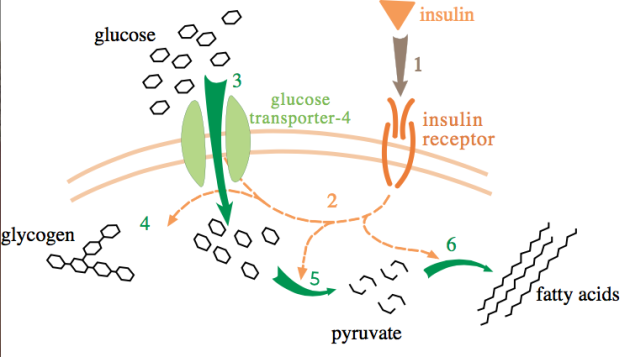

(2)When insulin comes into contact with the cell it stimulates the insulin receptor on the cells surface [1]. The insulin receptor stimulates many protein activation cascades inside the cell [2] including the translocation of the GLUT4 transport proteins (shuttles glucose into the cell) [3]. Once inside the cell, glucose has several options. It can be converted to glycogen (storage energy) [4], used as a readily available form of energy through glycolysis [5] or converted to pyruvate and used for fat synthesis (lipogenesis) [6].

Insulin Sensitivity

When we talk about carbohydrates and insulin, it’s really important to understand the concept of insulin sensitivity. Insulin sensitivity refers to how your body’s cells respond to the hormone insulin. People with high insulin sensitivity have better blood sugar control than people with low insulin sensitivity. If you chronically take in large amounts of carbohydrates, your pancreas will produce large amounts of insulin to clear this glucose and bring your blood sugar back down to homeostatic levels. The insulin receptors that stimulate glucose uptake by the cell will constantly be overworked and over time, will not respond as well as before. (3) This is called insulin resistance.

Your sensitivity to insulin is really a way to explain how your body responds to the carbohydrates in your system. Are they being taken up by cells (liver, muscle, fat) or are they floating around in your bloodstream for a while increasing your chances of becoming diabetic.

There are certain times when the body is more insulin sensitive. In the morning, just after waking, the cells are primed to take up glucose. At some point early in the morning, the hormones cortisol and epinephrine are released to break down stored glycogen to provide energy to “wake you up.” (4,5) Unfortunately, at this time muscle cells are not the only ones that are insulin sensitive. Fat cells are primed to take up glucose as well. (6) So while we are providing energy (carbs) for glycogen replenishment via the enzyme Glycogen Synthase and the amino acids necessary for new muscle protein synthesis, we are also providing an energy source for fat cells to add their cellular storage space- especially if we over eat.

Insulin Sensitivity After Exercise

The other time that the body is more insulin sensitive is following a training session by two mechanisms. (7,8)

First, exercise increases insulin’s action on glucose uptake by reducing the apparent Km and increasing the Vmax of the insulin-glucose reaction. (Note: Vmax and Km are physics terms of the Michaelis-Menten kinetics equations to represent rates and concentrations of enzyme reactions. Vmax represents the maximum rate achieved by the enzyme-substrate system at saturating substrate concentrations. Km is the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of the Vmax.) The increased insulin action may also be related to the exercise- induced increase in glycogen synthase activity.

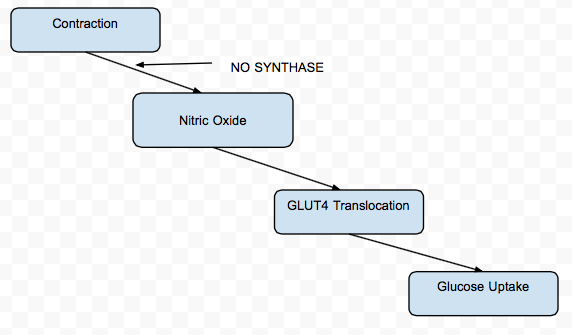

Secondly, muscular contraction increases muscle glucose transport in response to an acute bout of exercise. (9) Muscular contraction from exercise training leads to an increase in production of NO Synthase, an enzyme responsible for nitric oxide production. This results in beneficial adaptations in muscle tissue including an increase in GLUT4 protein expression. (10) This increase in GLUT4 activity contributes to an increase in the responsiveness of muscular glucose uptake to insulin. (8,9) The take home message here is that the GLUT4 transporters are more active following a training session and are more ready to “receive” glucose to store glycogen and rebuild new muscle tissue.

(11) So, back to the questions about the lack of carbs earlier in the day: I found that I did not suffer at all. Despite the fact that carbohydrates provide energy that will eventually become glucose to provide fuel for the body’s cells, I found that I am more alert and responsive when eliminating carbs from my earlier meals. There is no “surge” after breakfast and then a “lull” a few hours later. Interestingly enough, in animal studies on the diurnal changes in muscle and hepatic glycogen stores, researchers found that it was more preferable to ingest carbohydrate at night versus the morning when it came to having higher glycogen stores during the physically active times of the day. (12) In this study, eating carbohydrates during later meals of the day (i.e. after weight training for most of us) led to greater energy during the physically active parts of the following day.

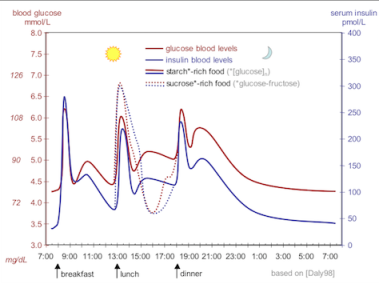

Another thing to look at for your breakfast is the effect the nutrients have on mood and cognition. Going to work with a groggy mind because you feel low on energy is no way to start your day. Studies show that a lower glycemic meal such as one without carbohydrates has positive effects on both mood and cognitive thinking when it comes to working memory and speed of processing. (13,14) This is because higher glycemic meals call for an increased insulin response. A lot of the time, due to the increased insulin sensitivity of muscle and fat cells in the morning, insulin will “over clear” the blood stream of glucose leading to a state called transient hypoglycemia. This is where your blood sugar dips below the normal amount and leaves you feeling tired for a little while until you eat again. By keeping your blood sugar stable with meals of proteins, healthy fats and veggies you avoid these ups and downs in energy.

Fat Loss

One last reason to avoid carbs in the meals farthest away from your training time is the effect that insulin has on fat loss. Insulin negatively modulates the enzyme hormone sensitive lipase (HSL). HSL breaks down stored fat (lipolysis) to be used for energy by the cells of the body. So when insulin is present, fat loss is blunted. (17) If your goal is to lose fat, you need to have periods of time where insulin is not being released. It makes sense to continue this lack of insulin and enhanced fat burning throughout the rest of the day until your body really needs carbohydrates, such as around your training time. Spreading your carbs out throughout the whole day evenly will lower your body’s fat burning capacity. If fact, lower fat, higher carbohydrate meals actually increase the levels of triacylglycerides circulating in the bloodstream after a meal- possibly due to the extra de novo lipogenesis or the reduced clearance of lipids from the bloodstream. (18,19) Taking in the majority of your carbohydrates after training in the evening can have an enhanced effect on your body fat and overall weight lost as well as cause an improvement to your insulin sensitivity. (20)

So to sum it up:

Prioritize your carbohydrate intake around your training time.

Assuming you train in the evening, rely on protein, healthy fats and vegetables for the earlier meals of the day.

You might notice enhanced cognition and be in a better mood when not eating carbs throughout the day.

Your blood sugar will be more stable.

Carbs later in the day will enhance serotonin production. This neurotransmitter is important for pleasurable sensations and improved sleep.

This plan might not be for everyone but has worked for many clients as well as myself. Some people can get away with more than others. Individual genetics and other lifestyle factors control this. If you are someone that trains first thing in the morning, you can still use this same strategy. Just take in the majority of your carbohydrates around your training time- maybe even intra-workout, and then rely on proteins, healthy fats and vegetables for the meals throughout the rest of your day.

And what’s in my breakfast: a mixture of free-range whole eggs, pasteurized egg whites, spinach and coconut oil.

To hire me for a more detailed, personalized plan, contact me at berryswole@gmail.com

References

-

Lamar-Hildebrand, N., L. Saldanha, and J. Endres. “Dietary and Exercise Practices of College-aged Female Bodybuilders.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 89.9 (1889): 1308-310. Pubmed.gov. Web. 28 Dec. 2013.

Insulin_glucose_metabolism_ZP.svg. Digital image. Wikipedia. Wikipedia, n.d. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

-

Kolterman, O. G., M. Greenfield, G. M. Reaven, M. Saekow, and J. M. Olefsky. “Effect of a High Carbohydrate Diet on Insulin Binding to Adipocytes and on Insulin Action in Vivo in Man.” Diabetes 28.8 (1979): 731-36. Print.

-

Fries, Eva, Lucia Dettenborn, and Clemens Kirschbaum. “The Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR): Facts and Future Directions.” International Journal of Psychophysiology 72.1 (2009): 67-73. Print.

-

Dodt, C., U. Breckling, I. Derad, HL Fehm, and J. Born. “Plasma Epinephrine and Norepinephrine Concentrations of Healthy Humans Associated with Nighttime Sleep and Morning Arousal.” Hypertension 1.1 (1997): 71-76. PubMed. 30 July 1997. Web. 21 Dec. 2013.

-

Wilcox G. Insulin and insulin resistance. The Clinical Biochemist Reviews. 2005;26:19–39.

-

Mikines, KJ, B. Sonne, PA Farrell, B. Tronier, and H. Galbo. “Effect of Physical Exercise on Sensitivity and Responsiveness to Insulin in Humans.” American Journal of Physiology 1st ser. 254.3 (1988): 248-59. Pubmed.gov. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.

-

Hawley, J. A., and S. J. Lessard. “Exercise Training-induced Improvements in Insulin Action.” Acta Physiologica 192.1 (2008): 127-35. Print.

-

Goodyear, PhD, Laurie J., and Barbara B. Kahn, MD. “Exercise, Glucose Transport, And Insulin Sensitivity.” Annual Review of Medicine 49.1 (1998): 235-61. Print.

-

Hansen, P. A., L. A. Nolte, J. O. Holloszy, and M. M. Chen. “Increased GLUT-4 Translocation Mediates Enhanced Insulin Sensitivity of Muscle Glucose Transport after Exercise.” Journal of Applied Physiology 85.4 (1998): 1218-222. Oct. 1998. Web. 5 Dec. 2013.

-

Lauritzen HP, Galbo H, Toyoda T, Goodyear LJ. Kinetics of contraction-induced GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle fibers from living mice. Diabetes 59: 2134–2144, 2010.

-

Suzuki, Masashige, Katsutoshi Ide, and Shin-ichi Saltoh. “Diurnal Changes in Glycogen Stores in Liver and Skeletal Muscle of Rats in Relation to the Feed Timing of Sucrose.” Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 29.5 (1983): 545-52. Print.

-

Cheatham, RA, SB Roberts, SK Das, and CH Gilhooly. “Long-term Effects of Provided Low and High Glycemic Load Low Energy Diets on Mood and Cognition.”Physiology and Behavior 98.3 (2009): 374-79. 7 Sept. 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2013

-

Halyburton AK, Brinkworth GD, Wilson CJ,, AK, GD Brinkworth, and CJ Wilson. “Low- and High-carbohydrate Weight-loss Diets Have Similar Effects on Mood but Not Cognitive Performance.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 86.3 (2007): 580-87. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.

-

Daly, M. E., C. Vale, M. Walker, A. Littlefield, K. G. Alberti, and J. C. Mathers. “Acute Effects on Insulin Sensitivity and Diurnal Metabolic Profiles of a High-sucrose Compared with a High-starch Diet.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 67.6 (1998): 1186-1986. Pubmed.gov. Web.

-

Suckale, Jakob. “Pancreas Islets in Metabolic Signaling – Focus on the Beta-cell.”Frontiers in Bioscience Volume.13 (2008): 7156. Pubmed.gov. Web. 30 Nov. 2013.

-

Meijssen, S. “Insulin Mediated Inhibition of Hormone Sensitive Lipase Activity in Vivo in Relation to Endogenous Catecholamines in Healthy Subjects.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 86.9 (2001): 4193-197. Pubmed.gov. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

-

Parks, Elizabeth J. “Changes in Fat Synthesis Influenced by Dietary Macronutrient Content.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 61.02 (2002): 281. Print.

- Wolever, Thomas M. S. “Dietary Carbohydrates and Insulin Action in Humans.” British Journal of Nutrition 83.S1 (2000): 97-102. Pubmed.gov. Web. 30 Nov. 2013.

- Sofer, S., A. Eliraz, S. Kaplan, H. Voet, G. Fink, T. Kima, and Z. Madar. “Greater Weight Loss and Hormonal Changes after 6 Months Diet with Carbohydrates Eaten Mostly at Dinner.” Obesity 19.10 (2011): 2006-014. Pubmed, 7 Apr. 2011. Web. 23 Nov. 2013.

-

Lamar-Hildebrand, N., L. Saldanha, and J. Endres. “Dietary and Exercise Practices of College-aged Female Bodybuilders.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 89.9 (1889): 1308-310. Pubmed.gov. Web. 28 Dec. 2013.

Insulin_glucose_metabolism_ZP.svg. Digital image. Wikipedia. Wikipedia, n.d. Web. 1 Dec. 2013. - Kolterman, O. G., M. Greenfield, G. M. Reaven, M. Saekow, and J. M. Olefsky. “Effect of a High Carbohydrate Diet on Insulin Binding to Adipocytes and on Insulin Action in Vivo in Man.” Diabetes 28.8 (1979): 731-36. Print.

- Fries, Eva, Lucia Dettenborn, and Clemens Kirschbaum. “The Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR): Facts and Future Directions.” International Journal of Psychophysiology 72.1 (2009): 67-73. Print.

- Dodt, C., U. Breckling, I. Derad, HL Fehm, and J. Born. “Plasma Epinephrine and Norepinephrine Concentrations of Healthy Humans Associated with Nighttime Sleep and Morning Arousal.” Hypertension 1.1 (1997): 71-76. PubMed. 30 July 1997. Web. 21 Dec. 2013.

- Wilcox G. Insulin and insulin resistance. The Clinical Biochemist Reviews. 2005;26:19–39.

- Mikines, KJ, B. Sonne, PA Farrell, B. Tronier, and H. Galbo. “Effect of Physical Exercise on Sensitivity and Responsiveness to Insulin in Humans.” American Journal of Physiology 1st ser. 254.3 (1988): 248-59. Pubmed.gov. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.

- Hawley, J. A., and S. J. Lessard. “Exercise Training-induced Improvements in Insulin Action.” Acta Physiologica 192.1 (2008): 127-35. Print.

- Goodyear, PhD, Laurie J., and Barbara B. Kahn, MD. “Exercise, Glucose Transport, And Insulin Sensitivity.” Annual Review of Medicine 49.1 (1998): 235-61. Print.

- Hansen, P. A., L. A. Nolte, J. O. Holloszy, and M. M. Chen. “Increased GLUT-4 Translocation Mediates Enhanced Insulin Sensitivity of Muscle Glucose Transport after Exercise.” Journal of Applied Physiology 85.4 (1998): 1218-222. Oct. 1998. Web. 5 Dec. 2013.

- Lauritzen HP, Galbo H, Toyoda T, Goodyear LJ. Kinetics of contraction-induced GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle fibers from living mice. Diabetes 59: 2134–2144, 2010.

- Suzuki, Masashige, Katsutoshi Ide, and Shin-ichi Saltoh. “Diurnal Changes in Glycogen Stores in Liver and Skeletal Muscle of Rats in Relation to the Feed Timing of Sucrose.” Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 29.5 (1983): 545-52. Print.

- Cheatham, RA, SB Roberts, SK Das, and CH Gilhooly. “Long-term Effects of Provided Low and High Glycemic Load Low Energy Diets on Mood and Cognition.”Physiology and Behavior 98.3 (2009): 374-79. 7 Sept. 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2013

- Halyburton AK, Brinkworth GD, Wilson CJ,, AK, GD Brinkworth, and CJ Wilson. “Low- and High-carbohydrate Weight-loss Diets Have Similar Effects on Mood but Not Cognitive Performance.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 86.3 (2007): 580-87. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.

- Daly, M. E., C. Vale, M. Walker, A. Littlefield, K. G. Alberti, and J. C. Mathers. “Acute Effects on Insulin Sensitivity and Diurnal Metabolic Profiles of a High-sucrose Compared with a High-starch Diet.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 67.6 (1998): 1186-1986. Pubmed.gov. Web.

- Suckale, Jakob. “Pancreas Islets in Metabolic Signaling – Focus on the Beta-cell.”Frontiers in Bioscience Volume.13 (2008): 7156. Pubmed.gov. Web. 30 Nov. 2013.

- Meijssen, S. “Insulin Mediated Inhibition of Hormone Sensitive Lipase Activity in Vivo in Relation to Endogenous Catecholamines in Healthy Subjects.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 86.9 (2001): 4193-197. Pubmed.gov. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

- Parks, Elizabeth J. “Changes in Fat Synthesis Influenced by Dietary Macronutrient Content.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 61.02 (2002): 281. Print.

- Wolever, Thomas M. S. “Dietary Carbohydrates and Insulin Action in Humans.” British Journal of Nutrition 83.S1 (2000): 97-102. Pubmed.gov. Web. 30 Nov. 2013.

- Sofer, S., A. Eliraz, S. Kaplan, H. Voet, G. Fink, T. Kima, and Z. Madar. “Greater Weight Loss and Hormonal Changes after 6 Months Diet with Carbohydrates Eaten Mostly at Dinner.” Obesity 19.10 (2011): 2006-014. Pubmed, 7 Apr. 2011. Web. 23 Nov. 2013.